A personal view – by Paul Whiteman, go-dan

Observations made in Japan taught me that in order to be considered a true member of a dōjō, purely turning up for practice on a regular basis was not enough. A true member requires a level of awareness of what is going on around him within the dōjō itself. Being mindful of the needs, wishes and expectations of your seniors and teachers alike, and to always put others first is fundamental. A difficult concept for us in the West but by no means impossible.

The simple act of sweeping and washing the dōjō floor before a practice session demonstrates an attitude of unselfishness worthy of any samurai in the past. In a dōjō there are teachers and there are students. It is the students responsibility to train hard and correctly so that all members of the group can advance in their Kendō. By ‘correctly’ I am talking in terms of posture, strikes, the use of ki-ken-tai, zanshin, and so on.

What all members must be especially vigilant of is the creeping in of bad habits such as bobbing and weaving the head like a boxer would. This kind of movement has no place in Kendō. By moving one’s head like this to avoid being hit will not only mess up your own Kendō but also cause your opponent and fellow classmates to have to alter their perfectly straight strikes in order to land a cut. It doesn’t take long before everyone is doing crap Kendō!

To inadvertently cause your classmates to pick up bad habits is wrong. You and your fellow students are all in the same boat and all share the same goal; that is to master the techniques of Japanese swordsmanship. A desire to gain respect from your teacher is also an important thing to have. A good teacher will always want his student to attain a higher level of Kendō even than themselves. A teacher, (whether it is a Kendō teacher or any other kind), will be able to spot straight away someone who is passionate about learning, so they will push that student harder, nurturing them as they go, praising them when they can demonstrate an understanding of what is being taught. A student without this hunger to learn and train hard will soon get left behind.

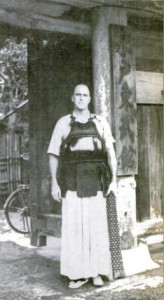

A dōjō can take on a ‘family’ element with socializing after practise sessions, especially if they are weekend sessions! There was a group of Kendōka from the All Japan Agricultural Corporation who used to come to the Soushinkan Dōjō (where I trained) on Saturday’s during my time in Japan. The practise session would start with thirty minutes kata followed by ninety minutes of kirikaeshi, kakari-geiko and a bit of ji-geiko at the end. Anyone who still had any energy left was made to do a final kakari-geiko from hell! I say ‘made to’, but in reality we all wanted to impress the owner of the dōjō , Kaneko-sensei, because it was he who made this dōjō possible. Getting back to this group of guys, they always brought with them a mountain of meat and vegetables that we would cook up at the dōjō and chaw down in sensei’s room. The beer and o-sake flowed and we juniors would always be ready to fill someone’s bowl or glass when it became empty. Evaporation is a huge problem in Japan! It was a pleasure to be part of that dōjō’s family atmosphere. Having to tidy up afterwards didn’t feel like a chore at all.

Being subservient to a certain degree is a good thing in a dōjō in England, but more so in Japan as the hierarchical system run deep. One of the hachidan sensei, by the name of Iwanaga-sensei, from Kitakyōshō, would drive fifty miles or so to our dōjō every Wednesday. He was a real character and if you were a few seconds late refilling his glass or lighting his cigarette, he would say: ‘No, too late! You had your chance!’ He was, of course, joking but he kept everyone on their toes. But it was this friendliness that was so appealing.

I, personally, am filled with a sense of gratitude to my seniors and teachers both here and in Japan for their help and support throughout my Kendō career. In the same way that we would be stuck if we didn’t have doctors or surgeons when we get sick, if we didn’t have our seniors and teachers to help us, our Kendō would stagnate into something that resembles a chicken fight. Appreciate what you have because a life without it doesn’t bear thinking about. A dōjō only exists because of its students. Even, on some occasions, you don’t fancy going to Kendō practise tonight, because you had a hard day or were stuck in traffic or something, just pick up your bogu, get into your car, drive to the dōjō and train! You’ll feel the better for it, I guarantee.