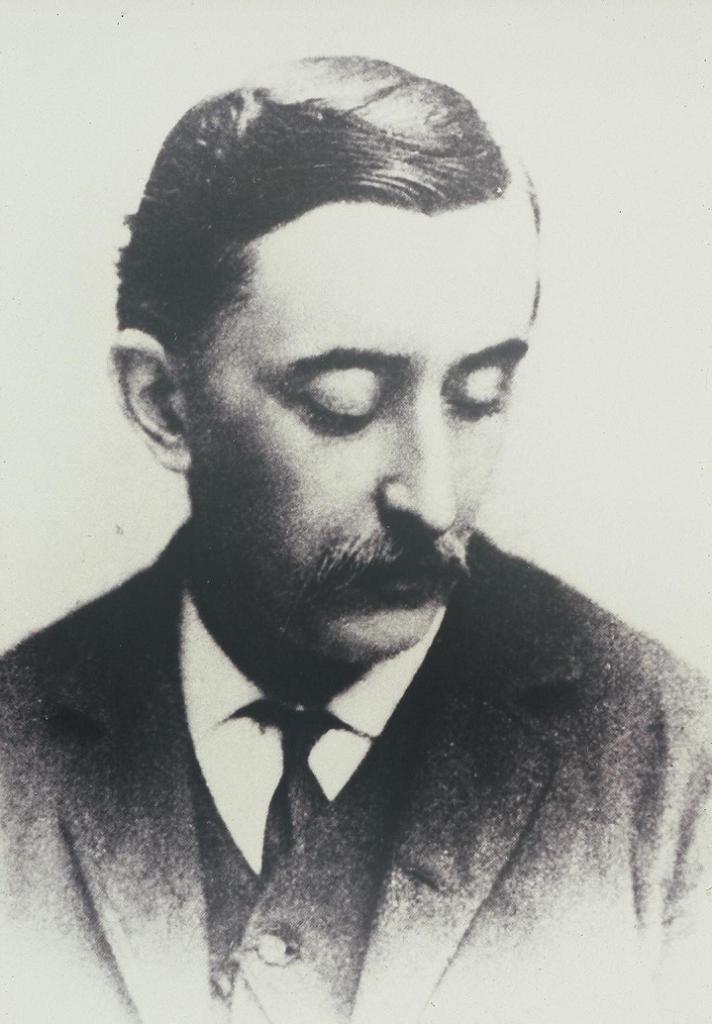

There is always pleasure in reading some authors who have taken a deep interest in subjects close to one’s own heart; this is particularly true of Japan since almost every writer seems to give a fresh insight into this fascinating culture. It doesn’t seem to matter if these writings were penned a hundred or more years ago, they come across the interval of time fresh and often stimulating. One of these authors was the remarkable Lafcadio Hearn who resided in Japan between 1890 and his death in 1910, precisely at a time when the Edō period was still a vivid memory to most of the population and this mediaeval culture had yet to be significantly influenced and modernised by outside events and ideas.

Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1910), better known to the Japanese by his adoptive name, Koizumi Yakumo, was originally of Greek extraction, but when he came to live in rural Iwate-ken in the backwater castle town of Matsue-shi he discovered and revealed a treasure-trove that engendered a huge interest in ‘things Japanese’ in the West. Whilst Hearn wrote about a very wide range of subjects that interested him, from everyday contact with colourful Shintō shrines, folk festivals, Buddhism and many more, he also retold things from the vivid memories in peoples’ minds of the often violent times of the Restoration period, (1858 – 1878) better known as the Bakumatsu-jidai, when the Tokugawa-bakufu was replaced by the Meiji government and the warrior class ceased to exist. In his collections, such as ‘Kwaidan‘ and

‘A Japanese Miscellany‘, can be found material that will deeply interest Kendōka who are immersed in the bugei (martial) traditions as they still survive.

Film buffs probably know that the Japanese director, Kobayashi Masaki, filmed ‘Kwaidan‘ famously in 1963; one of the four ghost stories told in this excellent film was ‘Hōshi the Earless‘ about a wandering priest who is forced by the ghosts of Heikei warriors who perished during the great sea-battle of Dan-no-ura-no-tatakai (25th April, 1185) to declaim the long poem describing the struggle . . . ‘The Heike-monogatari‘ . . . on pain of death. This poor man’s whole body was protected by holy characters from the Lotus Sutra but one ear was omitted . . . and this was torn off when the angry ghosts were thwarted.

Hearn’s house, built entirely in Japanese style, is eloquent of his status as an educator and stands alongside other preserved yashiki of senior samurai serving the important Matsudaira Clan who governed the fief. The house stands on the bank of the wide castle moat under the protection of Matsue-jō atop the rocky hilltop on the opposite side. The castle, which is one of only six throughout Japan, that survived destruction in Bakumatsu or during the last World War, was first constructed in stone in 1606, but was probably preceded by a more traditional wooden fortress dating from the sengoku-jidai. The present Prefecture has wisely preserved all these old residences, giving them museum status. Both banks of the moat are flanked by beautiful mature trees that are much favoured by flocks of nesting cranes, one of the symbols of longevity; above the castle donjon soar many red hawks, just as they did from the distant past. It is a quarter of this interesting city that one can still feel something of ‘Old Japan’.

Most of Hearn’s oeuvre is available in paperback form by Charles E. Tuttle Co. and highly recommended by the British Kendō Renmei.