Continued from part one.

One of the purposes of this article when first written, was to ‘open a window on the past’ and a mere recital of uncertain facts is no real way to do this. Who is really ‘livened up’ by dry as dust academic history other that some specialists? I was going to recount the historical background of the Kashima Shinto-ryu and the famous master, Tsukahara Bokuden, but will keep this back for a separate article on this Renmei Website in the coming months. We have a number of records, some fragmented, concerning this remarkable warrior but we must freely acknowledge that he was an undoubted genius and, despite his background in the bloody strife of his lifetime, he lived through most of the extreme virtual anarchy of the ‘Age of War’ throughout the first three-quarters of the Sixteenth Century, and his legacy is still very much with us today, more than five-hundred years after his death. His passing, in itself, is remarkable as he died in his bed at the age of eighty-two – and for a samurai of his time that was very unusual, indeed.

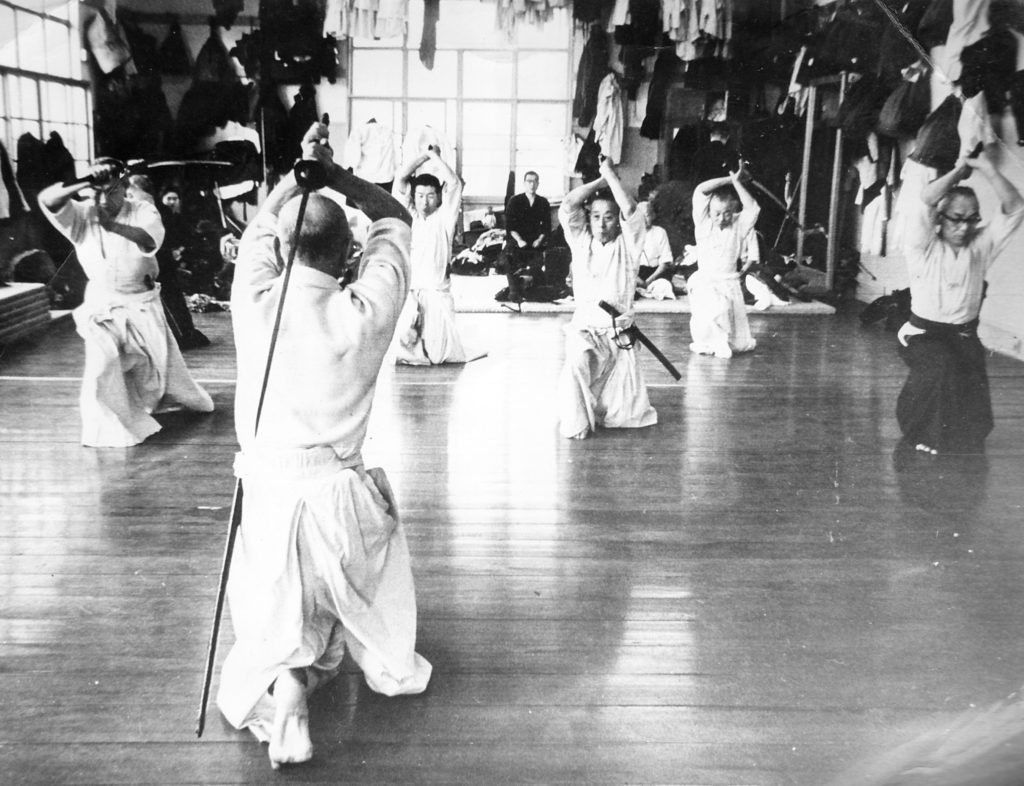

It is Bokuden’s legacy that I, personally, find so valuable in trying to understand the meaning of the Bugei, that brings it alive and makes it meaningful. Warfare is serious business and soldiers or warriors cannot be trained in the grim reality without what we term, in Japanese, kata, or ‘drills’. These forms encapsulate the understanding of many masters who have studied, often in battle, the techniques, the tactics, and the strategies of warfare in pre-arranged well-tested ways; these same skills were often handed down, revised, polished and perfected over hundreds of years. For most the objective was acquiring great skill at arms, ‘personal survival’, for the senior commanders the objective was command of their men on the battlefield the ‘survival of their lord and their clan’. For a very few, they aspired to true mastery – generalship. If the theories and practise didn’t work, the transmission died out and all was lost,; if successful, then we can still find the systems to-day. While we no longer need these skills for actual combat, the other side of the coin, though is physical fitness, alertness of mind, self-discipline, a proper regard for the rule of law, respect for others, strength of character, moral awareness – all to be found in the three or four core disciplines deriving from swordsmanship in Japan.

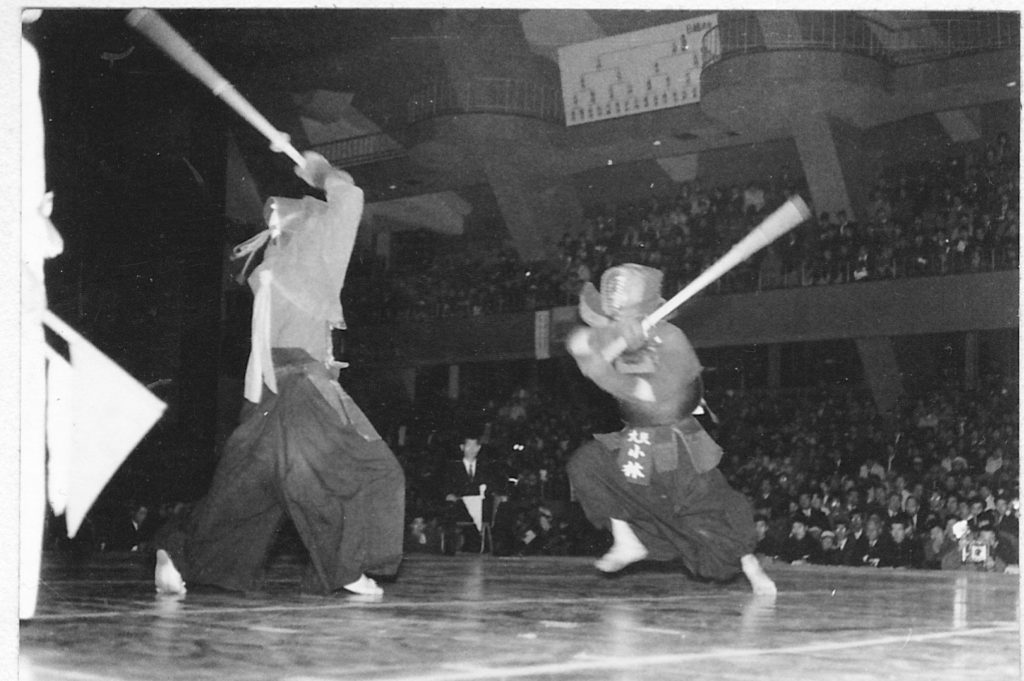

These mental and physical skills can be practised throughout life. They are not short-term in the sense of sport, although in youth some aspects make very good sport; they are long-term and continue and can be continued into advanced years through the decades, changing subtly as they progress. Bokuden-sensei was the first to realise and teach the difference between ‘the sword used to destroy’ and ‘the sword used to save life’ – a deterrent to disorder. In other words, amidst the chaos of his day, he saw the importance of the ‘Rule of Law’.

For his students of all ranks, he saw the value of skills leant through the discipline of practise, but for those who continued such training over many years, he saw the ‘freeing of the mind’ – the intuitive benefits of these skills.

Kata does not require physical strength, just a reasonable toned-up condition, but it does require the determination to succeed. In parallel with exercise it develops spirit and the ability for concentration – and it is really very interesting to all.

In conclusion to this brief overview of kata as it has come down to us from many surviving medieval warrior sources, it must be realised quite clearly that these ‘forms’ were, for most of their existence, vital military ‘secrets’ exclusively preserved and developed by the samurai. Their origins were not like those of nearly all ‘martial sport’ systems we see to-day. The ‘secret teachings’ of each of the many transmissions were a ‘matter of life and death’ and were a closed book to many of the students for many years. We are fortunate that a small part of this legacy has survived to the present day but the only way to learn is to find – and recognise – a sound teacher who can pass on something, within his understanding, of the real traditions.

There are nowadays many earnest books in English setting out the writings of a number of Japanese masters, some originals written or published centuries ago. Miyamoto Musashi’s ‘Book of Five Rings’ is regarded by some almost on a par with the Bible in the martial ‘arts’ field. Some translations are praiseworthy, but none really succeed in clearly explaining Musashi’s inner secrets of the art of war. The same criticism applies to the writings of such great masters as Yamamoto Kansuke (died 1561), Itō Ittōsai (17th Century), and many other famous swordsmen. These were secrets that were only revealed by ‘mouth to ear’ transmission, some printed, it is true, but not explained except to the most able and trustworthy students. Really my purpose here is to make the argument that from the arts of warfare handed down from the Japanese medieval times within these secretive martial systems, we have a very valuable physical, social, and moral legacy. We are fortunate not to have to use these often drastic techniques but we can gain great skills from safely practising them. Don’t mislead yourself and aim only for the top; very few have ever attained this summit. Just do your best to succeed and so come to understand yourself. Here in Kendo is just one way to do this but it is a path that can be followed one’s whole life through. You will find it brings great rewards.

One thought on “Understanding Kata – part two”